By ODIA OFEIMUN

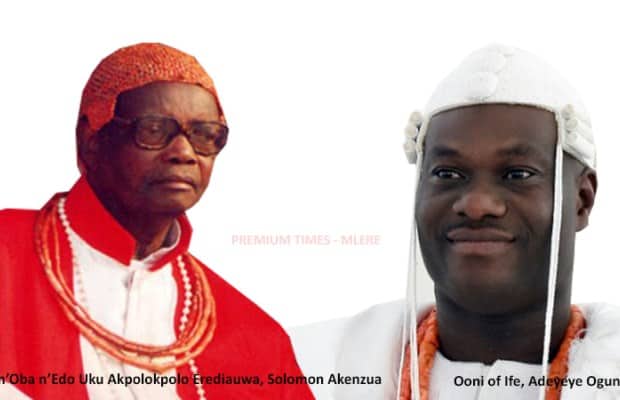

The truth of the matter is that even if anyone rejects the fact “that Ife Monarchy is derived from Igodo monarchy”, it changes nothing about the reality that the Monarchy in Benin City is still Number One among Oduduwa’s children. I mean: let it be assumed that Oduduwa came from Egypt, Mecca, Sudan, Ethiopia (where the Oromo Region has a nationality fraction called Oromiyas) or from Orun, as heaven or a place we do not know, with a chain made of iron if not some other metal, it does not change the fact that the dumb one who learnt to talk by naming himself Owomika, ‘my hand has stuck it’, the first Benin monarch after the Ogisos, was the first child of Oramiyan whose children built the empires that our part of the world remembers.

I am a Republican, not a Royalist. But, in a country in which we have all conceded the coexistence of Republican and Royalist values, it should be considered quite unseemly to watch one set of the interacting values being rough-handled, muddied or treated with improper decorum without feeling a need to intervene on behalf of rectitude. I have been so challenged since the eruption of the controversy ignited by the Alake of Egbaland, Oba Adedotun Gbadebo, who allowed himself to do a ranking of Yoruba Obas that placed the Oba of Benin as third in the hierarchy. In one sense, as Chief David Edebiri, the Esogban of Benin, immediately retorted, it is wrong to rank the Oba of Benin among Yoruba Obas because the Oba of Benin is not a Yoruba and therefore cannot be placed on a list of Yoruba Obas. I call it ‘in a sense’ because the Esogban’s position may be disputed on the grounds, as will soon be clear, that there is too much siblinghood between Yoruba and Benin traditional rulers for the ethnic difference between them to be rendered in cast-iron terms.

The special relationship between Yoruba and Benin obas, not unlike the relationship between Benin and Onitsha kings, or between Lagos and Edo kings, makes it all the more impolitic to do a ranking of the Benin monarchy in Yoruba royal affairs without abiding by certain inter-subjective and shared norms. And let me note, very quickly, that it is the presence of such norms that makes it quite normal for Chief Edebiri to put the Oba of Benin as Number One without appearing to contradict himself. In his response to the Alake, Chief Edebiri has argued, quite simply, that the term oba was not used to describe Yoruba kings until the Oba of Benin got there. This may well be disputed. Except that it has the merit of being close to verisimilitude when he argues that the king of Ibadan was called Olu, the king of Abeokuta was called Alake, the king of Oyo was called Alaafin; only the Benin monarch was Oba. With the backing of glotto-cultural studies, however, we should be able to impute that the term, Oba, is a root word shared by both the Yoruba and the Edo languages and that among the sixteen kings that reigned in Ile-Ife before the arrival of Oduduwa’s party, many had Oba as prefix to their names. To say this amounts to jumping ahead of the argument a little. But let me add, for those who are not familiar with this piece of anthropology, that Oduduwa, the acknowledged founder-ancestor, the progenitor of the Yoruba nationality, was a stranger who met a historical line of obas in Ile Ife, the last of whom was Obatala, the leader of the Igbo, the autochthons, later deified as god of creativity or creation, sometimes synced with Orunmila, for wisdom. Make your pick.

Let me also add that from the studies of the Ifa divination system made by several scholars, as imbibed from traditional Ifa devotees, it is those sixteen elders whom Oduduwa met in Ife that provided the sub-structure of Ifa as a formal system of wisdom into which people could be initiated in the way that we all go to tertiary institutions to learn philosophy, jurisprudence and mathematics. Or mathemagics, if you like. It is of very grave significance in this narrative that we should acknowledge that the Ifa Divination system, before the intervention of Islam, Christianity, and Lord Frederick Lugard’s balkanisation and regionalisation of traditional gnosis, was based on the existential patterns or prowess of the sixteen elders, or kings, who formed the planks upon which the wisdom of the people, by ritual accretions, was organised. Every good student of Ifa should know that in the Edo Divination system of Igwega, two of the sixteen elders have been displaced by Edo personages who are not to be found in the Ife version as designed by Agbonmiregun, the Master, who went from Ekiti to Ile Ife and established the rounded system of Ifa Divination as passed by other masters between the Edo, Nupe, Igala and Yoruba devotees. It can be imagined that, as a matter of ritual, they gathered at Ife, which was quite the centre of their world, for a divination that transcended ethnicities but was based on a common worship of the earth mother, Efa. All the forest peoples, from Dahomey to the Cameroon mountains, across the Nri of Igboland and past Ogoja, were devotees of one form or other of Ifa Divination. The historian, Ade Obayemi, has imputed that so many concepts in Yoruba Ifa, which some devotees may regard as mumbo jumbo, are actually Nupe terms that proper glotto-cultural analysis and translation could redeem. This partly explains why Benin Kings could induct or abduct and adopt Igbo medicine men who became part of the common national culture, as Egharevba, the Benin historian vouchsafes. What a linguistic, glotto-cultural analysis tells us is that in Ile-ife, before the dispersal occasioned by Oduduwa’s emergence, the Yoruba language, as one among many in the Kwa language complex, was once the same language with others including the Igbo and that they still share common root words beyond the simple ones like Omi and miri.

So if Chief Edebiri’s resort to linguistic analysis wont help a resolution of the ranking of the Yoruba obas, what will? I suppose it is the discomfort of trying to answer such a question, and the fear of being wrong-footed in a bid to dabble into what appears to be quite esoteric, that has warded off many of the dignitaries who have been asked by journalists to respond to the controversy. Some of them think it a needless controversy that could detract from more worthwhile issues of the moment. True, there are crying problems that our society needs to face and resolve. Some political entrepreneurs who require a united front in order not to disperse collective energies have been quick to advise against worsening of the already existing inter-ethnic divisions in our midst. Somehow, they do not consider that to ignore the controversy or down play its driven logic, could harden the ranking that has been attempted and, to that extent, make it quite affirmable with the accretion of time. Of course, those who are already convinced of its veracity and have lived in the shadow of its ritualised affirmation, all their lives, would want the ranking to remain as they know it. Hence, they act bored by the controversy and would therefore wish that we move on quickly to other matters. Unfortunately, (or fortunately, depending on how you see it) the controversy won’t go away.

It happens to be the case that the ranking of the Obas takes on a life of its own within every effort to build a sense of common nationality among Yoruba people. Every bid by the Yoruba to unite under a common leader or in conformity with a presumption of common ancestry, has always yielded one form of such ranking or the other. It has become part of a modernist or modernising project which nation-builders escape only when they are able to put the knowledge industry at the centre of their quest.

At any rate, this is not the first time it has visited or reared its head. The ranking, as it happens, is so deeply rooted in the ethnic unconscious of some people that there is good reason for the palace in Benin City to wish, with each eruption of the controversy, to put the records, or lack of records, straight. It happens to be the case that the ranking of the Obas takes on a life of its own within every effort to build a sense of common nationality among Yoruba people. Every bid by the Yoruba to unite under a common leader or in conformity with a presumption of common ancestry, has always yielded one form of such ranking or the other. It has become part of a modernist or modernising project which nation-builders escape only when they are able to put the knowledge industry at the centre of their quest. Especially, with the establishment of the Egbe Omo Oduduwa on home ground in 1948, the business of building up such a knowledge industry, creating a formal historiography to get it right, has been part of every bid at nation-building. With bounding successes in research and publications, everything seemed to be going fine before the regression that came with political crisis in the sixties and the virtual abandonment of the enlightenment project that Obafemi Awolowo is still rightly praised for.